Safety Service Patrol Business Models Strive to Meet Varying Needs

An inside look at centralized versus decentralized SSP programs

By Mindy Long

Forty states have Safety Service Patrols (SSP), yet how state agencies or other patrol operators administer those patrols within each state varies widely.

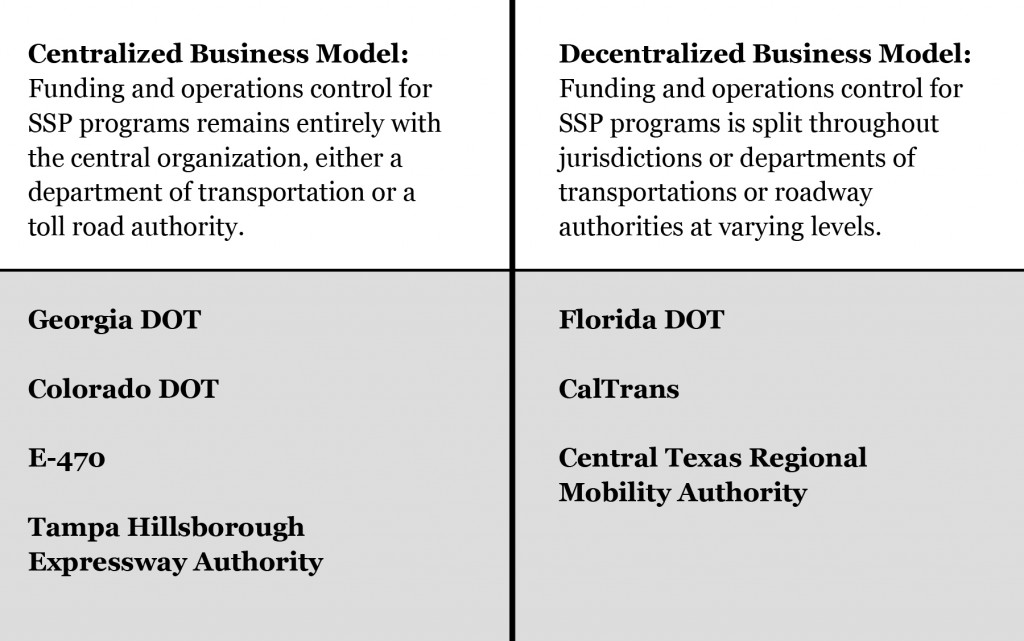

While many SSPs are funded and operated by state departments of transportation, others are funded and operated by regional metropolitan transportation authorities like the Central Texas Regional Mobility Authority, local toll road authorities like E-470 in Colorado or by a local government agency like the Transportation Agency for Monterey County. In many cases, these entities have varying levels of control over the funding and operating procedures of their SSPs.

Some states have instituted a centralized approach to funding and operations for SSPs in which the state department of transportation or toll road authority controls all aspects of the program from allocating appropriate funding to determining operation requirements to reporting on the program. The Georgia Department of Transportation (GDOT), for example, embraces a centralized business model that leaves funding and operational control of its Highway Emergency Response Operator (HERO) program in the hands of the DOT.

When faced with funding challenges it is the role of the DOT then to address these issues and find a viable solution. In 2009, GDOT sought a private sponsor to provide additional financial and promotional support of the program. Although, the sponsorship program now contributes $1.7 million per year to the patrol, the operational control remains entirely with GDOT.

When faced with funding challenges it is the role of the DOT then to address these issues and find a viable solution. In 2009, GDOT sought a private sponsor to provide additional financial and promotional support of the program. Although, the sponsorship program now contributes $1.7 million per year to the patrol, the operational control remains entirely with GDOT.

In Colorado the Department of Transportation (CDOT) also utilizes the centralized approach by directly funding patrols on I-70 and I-25 along with some other state and U.S. highways. Its model varies slightly from that of GDOT’s in that the state relies on one vendor and outlines certain operational requirements, such as driver uniforms.

The contractor reports directly to CDOT, and a CDOT project manager oversees program compliance. “We issue a Request For Proposals providing an opportunity to select a new contractor or the incumbent every five years. It’s competitive, based on low bid,” says Stacey Stegman, a spokeswoman for CDOT.

While CDOT’s SSP covers federally funded Interstates, the patrol does not cover the 47-mile toll road E-470 in Colorado. The E-470 Public Highway Authority directly funds and operates their SSP program. The Authority subcontracts toll operations , the communications center, EXpress Toll Service Center and SSP to Parsons Brinkehoff.

“We approve their [Parsons Brinkerhoff] budget, which includes funding for safety patrols,” explains Jo Snell, a spokeswoman for E-470. She added that the highway authority regularly reviews the provider’s expenses throughout the year.

“Parsons manages the whole safety patrol operation, but as their client, we are involved as needed in making suggestions, asking questions and reviewing actions when we feel the need,” Snell said.

GDOT, CDOT and the E-470 Public Highway Authority continue to successfully offer SSP services using the centralized approach to funding and operations. A different approach, however, has proven advantageous in Florida, California and Texas where state departments of transportation employ a decentralized approach to SSP funding and operations. This decentralized model requires state department of transportation to provide funding support to SSPs in the state with varying levels of control and input on SSP operations.

In Florida, the statewide SSP program, called Road Ranger, is divided into seven districts and each district is responsible for its own program. The Florida Department of Transportation provides funding, but each district can add discretionary funds if desired. In the Hillsborough, FL area, for example, FDOT provided $1,207,000 for the program, and the district added $2,103,137 in federal discretionary funds.

The FDOT creates a scope for the program that incorporates such items as uniforms, requisite equipment, specified training in traffic management and first aid, but each district prioritizes its needs and negotiates its own contract. “We may need more tow trucks because of the long bridges we have along the bays,” says Romona Burke, Intelligent Transportation Systems Support Manager for FDOT. Each district is responsible for oversight of their funding along with quarterly reporting to the central office.

Although each district covers its major roadways, the state contract didn’t have a provision to provide a Road Ranger for the toll road SR 618. The Tampa Hillsborough Expressway Authority (THEA) that operates the toll road faced a unique funding challenge when seeking budget approvals for an SSP. Fortunately, Burke explained, many state contracts have cross operating provisions that allow other agencies to utilize the contract, so THEA was able to take advantage of previously negotiated rates and terms.

While THEA benefited from the existing FDOT contracts, funding and operational controls remain with the authority. Like E-470 in Colorado, THEA is a separate and discreet authority from the department of transportation and utilizes a centralized model rather than the decentralized model embraced by FDOT to fund and manage its patrols. “We have the backstop of a bigger organization, but by directly funding the program, we have operational control over our Road Ranger,” said Susan Chrzan, a spokeswoman for THEA. Because FDOT outlines the scope of the program in its state contract, consistency across the jurisdictions and on State Road 618 exists in terms of program services, but not program management.

A decentralized model in Texas finds independent authorities in multiple regions operating SSPs. “Due to budget constraints, the state has been reducing or eliminating safety patrols and it has been left up to local communities to decide if they want to fund those patrols with the money they’re allocated,” said Steve Pustelnyk, a spokesman for the Central Texas Regional Mobility Authority (CTRMA).

With this decentralized approach, funding sources can vary by region. In Austin, the Texas DOT had cut funding for their Highway Emergency Response Operator (HERO) Program along a 31-mile stretch on I-35. “There were a number of folks in the community who felt that was a valuable program and wanted to restore it,” Pustelnyk says. When money allocated for transportation projects became available via the federal American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, the program was reestablished. The current program is funded with $1.8 million in American Recovery and Reinvestment Act stimulus funds, which are expected to run out in August. The funds came through TxDOT and were allocated by a metropolitan planning organization—a federally required regional transportation planning organization. “TxDOT is considered a partner but they have mainly assumed an oversight role in regard to accounting for the federal and state funds,” Pustelnyk says. He adds that the CTRMA sets the standards for the program, but has to adhere to certain reporting requirements depending on the funding they’re using. The Authority also measures the benefits of the program. Pustelynk says they have found funding that will keep the program going for several more years through the metropolitan planning organization.

The state department of transportation in California, CalTrans, also uses a decentralized model in that it works with local government agencies to fund and operate its Freeway Service Patrols (FSP). CalTrans provides the majority of the funding for the FSP program, but local government agencies, like the Transportation Agency for Monterey County, also provide funds.

CalTrans generally contributes 80 percent of the funding for the program. “We supply the other 20 percent with unused local call box program revenues, which originate from $1 vehicle registration fee collected by the Department of Motor Vehicles,” explains Kaki Cheung, Associate Transportation Planner for the Monterey County agency.

CalTrans and local government authorities operating Freeway Service Patrols work together in the creation and submission of performance reports. As an example, the Transportation Agency for Monterey County provides a quarterly summary to the drivers and the highway patrol and an annual report for CalTrans. In turn, CalTrans produces a bi-annual report for the agencies and provides a benefit to cost ratio. “It is a very complicated model they have developed. They look at the assist data we provide and they assign values to where the accident or incident occurred,” Cheung says. She adds that incidents occurring in a travel lane receive higher points than those occurring on the shoulder. “They assign the value to the cost of driving, vehicle delay and they assign costs to the environmental benefits.”

CalTrans also provides consistency in FSP operations and procedures throughout the state. Because there are different managers working on the program in each area, standard operating procedures help minimize any discrepancies in the operations. Driver uniform requirements and the drivers’ responsibilities are all outlined by the state.

“We talk about alcohol and drug policies, drivers’ main responsibilities, how they should act with the motorist, how they should operate the tow truck that they’re driving,” Cheung said. “All the drivers in the program go through a certification program and training that is done by the highway patrol, so we’re starting with a level playing field.”

CalTrans and the state highway patrol review the state’s standard operating procedures annually. The Transportation Agency for Monterey County meets with drivers on a quarterly basis. “We meet with the other local agencies across California at least once a year to talk about the different issues we’re facing to keep a continuous coordination,” Cheung said.

While the coordination across jurisdictions is a benefit to the overall FSP program and to traveling motorists, Cheung values the control the local agency still has over its FSP program. She likes the local flexibility that comes with California’s decentralized model. “The local agencies are the ones in tune with what is going on in their area. We provide additional services if there is something special going on during the weekend, like an event, to help reduce traffic jams or clear accidents,” Cheung explains. “If there is construction and we know a shoulder is going to be blocked, we see a benefit to having our drivers out there to assist.”

CTRMA’s Pustelynk agrees and says the biggest advantage of the similarly decentralized approach he is utilizing is the local control, the ability to prioritize which corridors are most in need of the service and determining if it is worth continuing. However, the funding disadvantages remain since the TxDOT has previously had to reduce or eliminate SSPs due to funding challenges. “It can lead to some degree of funding uncertainty because there isn’t a standing, secure revenue source,” Pustelynk said.

With funding uncertainties resolved, THEA’s Chrzan is happy with the current arrangement. Not only does the state contract ensure Chrzan gets the lowest rates for THEA’s Road Ranger, it also ensures the Road Ranger’s training, such as first aid and maintenance of traffic training, is consistent with that of other Road Rangers in the state.

“It is really important for the safety of the Road Ranger and the safety of the motorists he [or she] is helping,” Chrzan says. “I personally think my way of working it works best. I have a statewide contract and a countywide pool, but [the Authority] is in control of the Road Ranger on its road.”